Exaggeration in sebum production is demonstrated in semblance as what we most notoriously recognize as oily skin. However, sebum in substance seems to be vitally rich and precious so that in disease state its composition is first imperiled even before changes in its quantitative order. Sebaceous glands production and function has been examined early in the context of acne pathogenesis research and its subjugation is still one of the leading areas of study in acne vulgaris management. Coming up with a protocol for treatment of acne requires understanding of acne mode of development. Although, the precise mechanisms of acne are not known, it is generally accepted that there are four major factors involved in development of acne [1]:

1. An increased sebum production under androgen influence [2].

2. Ductal hypercornification (hyperproliferation of ductal epidermis) Hypercornification is overproduction of epithelial cells lining follicles (sebaceous ducts, these ducts conduct sebum to the skin). Hypercornification of pilosebaceous ducts can be seen histologically as microcomedones [3].

3. Bacterial colonization of the duct with Propionibacterium acnes, now known as Cutibacterium. acnes, C. acnes.

4. Further production of inflammation in acne sites, perifollicular inflammation [4] [5].

Acne and sebum production: Several factors influence sebum production, but it is predominantly hormonally stimulated which guides hormonal therapy in acne. Androgens especially from the testes and adrenals, stimulate the sebaceous gland directly and influence acne inflammation. Sebacous glands are recognized as an endocrine organ as seobocytes possess androgen nuclear receptors, implicated in sebocyte differentiation and apoptosis.

Diacylglycerdies have been found to be increased in acne vulgaris whether as a direct result of triglycerides catabolism or their defective anabolism under influence of propriobacterium.acnes. A study comparing lipid composition of individuals with and without acne elucidated a higher level of squalene, 2.2 times, in acne patients while other major sebum lipid classes did not show any statistically significant difference between the two groups.

In addition, the skin and its appendages , including hair follicles and sebaceous glands are armed with all the necessary enzymes required for androgen synthesis [6]. Two major enzymes work to produce androgens are 5-alpha reductase [7] and steroid sulfatase [8]. In contrast, aromatase inactivate the excess androgens locally in order to achieve androgen homeostasis [9]. In the skin the activity of the type1 5-alpha-reductase is concentrated in sebaceous glands and is significantly higher in sebaceous glands from the face and scalp compared with non-acne-prone areas [10]. Estrogens exert a variable inhibitory effect in pharmacological doses.

Specific enzyme expression and activation in cultured seboyctes and keratinocytes seem to allocate different duties to these cells in vitro. Sebocytes are able to synthesize testosterone from adrenal precursors and to inactivate it in order to maintain androgen homeostasis, whereas keratinocytes are responsible for androgen degradation [9].

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors, PPAR, are categorized as nuclear hormone receptors which form a dimer with retinoid X receptor and function in transcriptional regulation of genes involved in inflammation and lipid metabolism in the skin, liver and adipose tissue. Known with isoforms, α, δ and γ, their activating ligands are fatty acids and other lipids. However, androgens in vitro have shown no similar effects (androgen synthesis). This suggests a role for cofactors such as PPAR ligands such as linoleic acid.

Catalytic effect of PPAR (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor) ligands were shown on cellular testosterone activation by which can regulate sebaceous lipids [11]. PPAR ligands such as Zileuton or rosiglitazones induce lipogenesis and increase sebum production [12]. Sebum excretion is significantly greater in patients with cysts and attempts pharmacologically to reduce the sebum production are a logical approach to acne management.

The sebaceous glands ( part of sebaceous follicles ) are under endocrine control and so it is not surprising that sebum production shows change according to age and sex of an acne patient. Sebum production is dramatically greater than that in females in normal individuals as well as acne patients. There is an increase in sebum production with a peak at about age 40. Any approach to control androgens appear to be relevant to adult acne since the sebaceous follicle ( sebaceous glands are located in the dermis, the middle layer of skin, secrete oil onto the skin and their overfunction may stoke an increase in skin’s oil production) is an organ targeted by androgens.

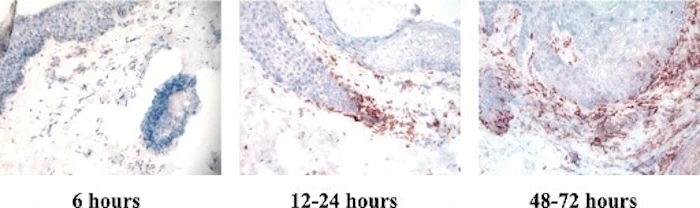

Progression of TLR-2 expression in acne according to the evolution of the lesion. After 6 hours only a few TLR2 positive cells were detected. However, the number of TLR2 positive cells continue to increase with time [40]. Skin surfaces in the acne prone areas are colonized with Staphylococcus epidermidis and Cutibacterium acnes, C. acnes, which play a critical role in development of acne and changes in sebum production [19].

Several mechanisms may explain role of C. acnes in development of acne [20]. One mechanism seems to be direct effect of C. acnes on keratinocytes through interaction with toll like receptors TLR-2 and TLR-4, which leads to release of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1alpha and beta, IL-8, GM-CSF and TNF-alpha [21] [22].

Increase in TLR2 positive cells with time in acne vulgaris. Toll-like-receptor-2 positive cells populate with aggravation of acne disease

Studies suggest that bacteria have nothing to do with the initiation of comedogenesis. However, C. acnes, in particular, may in some situations be important in the initiation of inflammation. It is also quite likely that they are involved in a perpetuation of inflammation once established. Recent studies far more lean toward the notion of dysbiosis, transformation in the skin microbiome in clonal diversity as well as relative excess rather than time-worn bacterial colonization which seems to outlive its accommodative state. Role of dysbiosis in the intrinsic skin microbiome has been substantiated in atopic dermatisis, rosacea, psoriasis and acne vulgaris by sustaining a change in the population of the skin commensal bacteria.

Under anaerobic conditions, C. acnes catalyzes triacylglycerols in the sebum to short-chained free fatty acids, SCFAs, which efficiently hamper S. epidermidis to generate biofilms and restore its antibiotic sensitivity, an instance which readily illustrates how one commensal satisfactorily curbs the other and how an offensive dysbiosis may give rise to a disease state.

Hyper proliferation of ductal epidermis, histologically seen as microcomedones, is associated with development of adult acne. There is a significant correlation between the severity of acne and number and size of microcomedones [3]. A possible drive to pilosebaceous duct hypercornification could be hormones, in particular androgens [13]. Androgens exert their effect through dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which is primarily responsible for androgen receptor binding and exerting end-organ effects [14]. In sebaceous glands, androgen receptors are identified in basal and differentiation sebocytes [15].

Overall levels of 5-alpha-reductase, converting testosterone to DHT, have been shown to be higher in the sebaceous glands of patients with acne than those without acne [16]. In addition, retinoids, vitamin A, vitamin D, insulin and IGF-1 are among most important mediators of sebocyte either differentiation or proliferation, associated with sebum profusion.

Qualitative or quantitative alteration in the sebaceous lipids translates into a milieu predisposed to keratinocyte proliferation and comedogensis and elevated sebum production. Lipid peroxidation is one example, amid multitude, which may lead to sebum shifts by production of squalene peroxide known to invoke proinflammatory cytokines and PPARs, in particular PPARα and PPARγ.

Central to sebocyte homeostasis, PPARα modulates beta oxidation of fatty acids and PPARγ, the major PPAR expressed on sebocytes, contributes to lipid synthesis. While lipids in large are major ligands for PPARs, HETEs and leukotrienes, products of LOX, lipoxygenase, on arachidonic acid, function as other ligands. LOX metabolites are implicated in various inflammatory disorders as well as cell proliferation, differentiation of various cell lineages, among them keratinocytes as increased 12-HETE was found in psoriatic skin.

Burgeoning evidence proposes a link between inflammation and sebaceous gland lipid synthesis, demonstrating enhanced expression of LOX-5, lipoxygenase-5, and COX-2, cycloygenase-2, expression on sebocytes in acne patients compare to those of controls, simultaneous with increased upregulation of IL-6, IL-8, LTB-4, PGE2 under the yoke of PPARγ, the primary PPAR expressed in sebocytes.

The adult acne inflammation is not, in most cases, an abnormal response of the immune system. The inflammation represents a normal immune and non-immune response to foreign substances penetrating the dermis. Department of dermatology of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein suggested keratinocytes express anti-microbial peptides constitutionally and upon injury or infection, e.g. by stimulation of TLRs (toll like receptors) through PAMPs and DAMPs [23]. However, the skin can also be a site of excessive immune responses as part of the innate immune response [24]. Therefore, the skin must ensure an efficient defense against pathogens and withal minimize excessive immune responses which can result in disease states.

From the other hand, within the duct, variations in the lipid composition have been put forward to explain comedones ( an initial acne lesion ) formation, which could be either closed (whiteheads, see photo) or open (blackheads). Sebum analysis indicates variations which include an increased concentration of squalene, squalene oxide, and certain fatty acids. This change in qualitative change in sebum lipids induce alteration of kertinocyte differntiation and induce IL-1 secretion, contributing to the development of follicular hyperkeratosis [17].

A decrease in the linloleic acid fraction of the skin surface lipids has been shown in a patient with acne. Hints that omega-3 fatty acids might positively influence acne originate from older epidemiological studies which show that communities that maintain a traditional diet high in omega-3 fatty acids have low rates of acne [18].

Keratinocytes play an important role in the inflammatory reaction of the skin, synthesizing a number of cytokines, adhesion molecules and growth factors which in one way or another affect sebum production [25]. Sebaceous glands and sebocytes in culture were shown to produce IL-1alpha [26]. in The cytokines that proved essential at the onset of inflammation and during an innate immune response include proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1) [27]. Keratinocytes essentially express inflammasone proteins as well as proIL-1alpha and beta, which can be transformed to active forms by certain conditions such as UV irradiation , associated with increase in sebum synthesis and acne aggravation[28].

Interactions between IL-1, sebaceous hyperproliferation and P.acnes. Comedo formation is associated with increase in IL-1alpha and becomes more inflammatory with colonization of P.acnes. Inflammation could be initiated through mediation of CD4+ T-cells or by a more nonspecific mechanism through involvement of cytokines such as TNF-alpha. [29].

Research by Zouboulis group showed that patients with severe acne having nodules and cysts have been benefited by a treatment with anti-inflammatory agents such as corticosteroids [32]. Enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of the proinflammatory lipids leukotriene LTB4 and prostaglandin-E2 are activated in sebceous gland of acne lesions [33]. LTB4 is now known to up regulate sebm production and synthetic inhibition of LTB3 in the form of drug zileuton leads to significant improvement in acne [34]. Fish oil EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and GLA (gamma-linolenic acid) have been reported to inhibit the conversion of arachidonic acid into LTB4 to the same degree as the LTB4-inhibiting acne drug candidate zileuton [35].

Study by Yosipovitch et al, cast doubt on existence of a direct link between stress and quantitative sebum levels, however, a positive correlation was found between stress experienced by male patients and severity of acne lesions, which may be attributed to alteration in sebum composition rather than its produced amount as well as neuropeptide secretion, suggestively CRH.

Addition of DHT to cultured sebocytes has been demonstrated to increase immunoreactity of IL-6 and TNF-alpha [30]. TNF-alpha induces lipogenesis in SZ95 human sebocytes through the JNK (c-Jun N-terminal Kinase) and phosphoinositide-3-kinase pathways [31].

Polyphenols have been suggested to down-regulate sebaceous gland metabolism and attenuate increase in sebum synthesis associated with acne. UVA, visible light and infrared have been found to be effective in control of sebaceous lipids and their contribution in pathogenesis of acne vulgaris, without invoking epithelial inflammatory response.

Sebocytes express leptin, an adipokine, receptors which lead to accumulation of lipid droplets within the cells upon activation and account for leptin implication in sebum production. Since leptin serum level enhances with increased lipid uptake, an association between diet and acne vulgaris may be perpetrated as a repertoire of studies by distinct mechanisms have alluded. On the other hand, leptin upregulate STAT-3, NF-κB and increase IL-6 and IL-8 and provocate an inflammatory state within pilosebaceous units.

Skin seems to be equipped with necessary enzymes involved in androgen synthesis. 5-alpha-reductase, steroid sulfatase, HSD1 (hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase) and HSD3 are all available at sebaceous glands level. Aromatase also involves at the skin level to maintain homeostasis [6]. Among non-steroidal inhibitors of 5-alpha-reductase, zinc, isoflavanoids, gamma-linolenic acid could be named. Genistein, thiozolidinediones are examples of non-steroidal inhibitors of HSD3 [6].

Androgens may be the initial trigger of a change in the skin that may lead to alteration in sebum production and comedone/acne formation. Androgens implement their effect by eliciting an inflammatory response and by increasing lipogenesis concurrent with change in the skin lipid composition at sebocyte level. The alteration in skin surface lipid composition provokes an inflammatory response and provides an environment more prone to C.acnes colonization.

P.acnes itself is responsible for exaggerating inflammatory response by inducing an acute, transient transcriptional inflammatory response in keratinococytes, suggested by a comparative global-transcriptional analyses for P.acnes infection of keratinocytes [36]. C.acnes contributes to the inflammatory nature of acne by inducing monocytes to secrete proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-alpha, IL-1Beta and IL-8 [37]. C.acnes triggers inflammatory cytokine responses in acne by activation of TLR2, which may be a potential target for isoflavanoids [38].

Research of the skin research center at Leeds, headed by professor J.H Cove proposed that onset of sebum synthesis in sebaceous glands and consequently expansion of the propionibacterial skin flora occur earlier in children who develop acne than in children of the same age and pubertal status who do not develop acne [39]. This study does not explain if this phenomenon is independent of androgens and if this occurrence should be counted as role of genetics factors as predisposing to this event.

It seems that there exist multiple predictable dialogues among various factors that in one way or another contribute to acne/comedone development. Alteration in androgen levels, change in lipidogenesis and sebum output qualitatively and quantitatively, inflammatory response, keratinocyte proliferation, bacterial colonization and lipid peroxidation by free radicals, sebocytes proliferation and differentiation are not static processes and sustain a manifold dynamism vulnerable at number of sites and amenable to multitude of therapeutics. The persistent interactions of these factors fluctuates course of acne vulgaris, which, seemingly, press for an all-encompassing treatment targeting every element of this interactive cycle and not over-zealously banking on one single aspect of the ailment complex sketch.

The multifactorial nature of sebaceous gland dysregulation necessitates a nuanced understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms of sebum overproduction and its downstream effects on cutaneous homeostasis, particularly in chronic inflammatory dermatoses such as acne vulgaris, seborrheic dermatitis, and rosacea-associated sebaceous hyperplasia. The role of androgen-mediated sebaceous gland activity—through upregulation of 5-alpha-reductase, increased dihydrotestosterone (DHT) signaling, and downstream activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARγ)—is central to this discussion, as these elements collectively amplify lipid biosynthesis in sebocytes, promote keratinocyte hyperproliferation, and establish a pro-inflammatory milieu within pilosebaceous units.

From a translational research standpoint, interventions targeting sebaceous lipogenesis, such as PPARγ inhibitors, androgen receptor blockers, or agents modulating lipoxygenase pathways, offer a therapeutic window not just in hormonal acne, but also in broader clinical phenotypes involving sebaceous gland hyperplasia and seborrheic skin conditions. Longitudinal studies suggest that changes in sebum composition—such as elevated squalene peroxide and depleted linoleic acid levels—serve as initiating events in comedogenesis and IL-1α–driven follicular hyperkeratinization, which represents a key therapeutic target for novel topical anti-acne formulations.

Further compounding the inflammatory cascade is the presence of Cutibacterium acnes–induced dysbiosis, where alterations in the cutaneous microbial ecosystem trigger activation of toll-like receptors (TLR2, TLR4), resulting in overexpression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-8. These cytokines are critical in sustaining the perifollicular inflammation that characterizes not only nodulocystic acne but also refractory adult-onset acne. The evolving concept of microbial dysbiosis rather than simple colonization highlights the therapeutic potential of microbiome-modulating treatments, including targeted bacteriotherapy, antimicrobial peptides, or even selective quorum sensing inhibitors.

Importantly, recent insights into stress-induced sebaceous gland responses—particularly via CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone) and adipokines like leptin—reveal an additional neuroendocrine axis that regulates both sebum quality and inflammatory thresholds. This supports the clinical rationale for integrative strategies combining anti-inflammatory, sebum-regulating, and barrier-restoring approaches to effectively address acne-prone oily skin in both adolescent and adult populations.

The intersectionality of androgen-driven lipid metabolism, immune dysregulation, microbial imbalance, and keratinocyte signaling demands a systems-biology approach in developing multimodal topical therapies for seborrheic skin disorders, especially those marked by excessive sebum production, altered skin lipid composition, and chronic inflammation of pilosebaceous units.

1. Winston MH, Shalita AR. Acne vulgaris, pathogenesis and treatment. Peddiatr Clin North Am. 1991;38:889-903.

2. Thiboutot, DM. Overview of acne and its treatment. Cutis. 2008;81(1S):3-7.

3. Cunliffe WJ, Holland DB, Jeremy A. Comedone formation: Etiology, clinical presentation and treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(5):367-74.

4. Holland DB, Jeremy AH. Review, the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of acne and acne scarring. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2005;24(2):79-83.

5. Zouboulis CC, Schagen S, Alestas T. Review, the sebocyte culture, a model to sutdy the pathophysiology of the sebaceous gland in sebostasis, seborrhoea and acne. Arch Dermatol Res. 2008;300(8):397-413.

6. Chen WC, Thiboutot D, Zouboulis CC. Cutaneous androgen metabolism: basic research and clinical perspectives. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:992-1007.

7. Eicheler W, Dreher M, Hoffmann R, Happle R, Aumuller G. Immunohistochemical evidence for differntial distruibution of 5alpha-reductase isozymes in human skin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:371-6.

8. Milewich L, Shaw CB, Sontheimer RD. Steroid metabolism by epidermal keratinocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;548:66-89.

9. Fritsch M, Orfanos CE, Zouboulis CC. Sebocytes are the key regulators of androgen homeostasis in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116(5):793-800.

10. Thiboutot D, Harris G, Iles V, Cimis G, Gilliland K, Hagari S. Activity of the type 1 5-alpha-reductase exhibits regional differences in isolated sebceous glands and whole skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:209-214.

11. Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Testosterone metabolism to 5-alpha-DHT and synthesis of sebaceous lipids is regulated by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligand linoleic acid in human sebocytes. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(3):428-32.

12. Trivedi NR, Thiboutot DM, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors increase human sebum. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:

13. Strauss JS, Kligman AM, Pochi PE. The effect of androgens and estrogens on human sebocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:139-155.

14. Mercurio, MG, Gogstetter DS. Andrgoen physiology and the cutaneous pilosebaceous unit. J Gend Specific Med. 2000;3:59-64.

15. Hodgins MB, Van der Kwast TH, Brinkmann AO, Boersma WJ. Localization of androgen receptors in human skin by immunohistochemistry, implications for the hormonal regulation of hair growth sebaceious glands ans sweat glands. J Endocrinol. 1992;133:467-75.

16. Sansone G, Reiser RM. Differntial rates of conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone in acne and in normal human skin, a possible pathogenic factor in acne. J Invest Dermatol. 1971;56:366-72.

17. Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Zouboulis CC, et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(10):821-32.

18. Logan AC. Linoleic and linolenic acids and acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(1):201-2.

19. Ingham E. The immunology of propionibacterium acnes and acne. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1999;12(3)191-7.

20. Vowels BR, Yang S, Leyden JJ. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines by a soluble factor of propionibacterium. acnes. Implications for chronic inflammatorory acne. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3158-65.

21. Nagy I, Pivarcsi A, Koreck A, Szell M, Urbn E, et al. Distinct strains of Propionubacterium acnes induces selective human beta-defensin-2 and interleukin-8 expression in human ketratinocytes through toll-like receptors. J Invvest Dermatol. 2005;124:931-8.

22. Graham GM, Farrar MD, Cruse-Sawyer JE, Holland KT, Ingham E. Proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes stimulated with p.acnes and p.acnes GreEL. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:421-28.

23. Glaser R, et al. Antimicoribal psoriasin (S100A7) protects human skin from Escherichia coli infection. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(1):57-64.

24. Nestle FO, et al. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(10):679-91.

25. Partridge M, Chantry D, Turner M, Feldman M. Productionn of IL-1 and IL-6 by human keratinocytes and squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:771-76.

26. Zouboulis CC, Xia L, Akamatsu H, Seltmann H, Fritsch M, et al. The human sebocyte culture model provides new insights into development and management of seborrhea and acne. Dermatology. 1998;196:21-31.

27. Feldmeyer, et al. Interleukin-1, inflammasones and the skin. Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89(9):638-44.

28. Feldmeyer L, et al. The inflammasone mediates UVB-induced activation and secretion of interleukin-1beta by keratinocytes. Curr Biol. 2007;17(13):1140-5.

29. Farrar MD, Ingham E. Acne: Inflammation. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(6):380-4.

30. Lee WJ, Jung HD, et al. Effect of dihydrotestosterone on the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines in cultured sebocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302(6):429-33.

31. Choi JJ, Park MY, Zouboulis CC, et al. TNF-alpha increases lipogenesis via JNK and PI3K/Akt pathways in SZ95 human sebocytes. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;65(3):179-88.

32. Bass D, Zouboulis CC. Bhandlung der acne fulminants mit isotretinoin und prednisolone. Z Hautkr. 2001;76:473.

33. Alestas T, Ganceviciene R, Fimmel S, Muller-Decker K, Zouboulis CC. J Mol Med. 2006;84(1):75-87.

34. Zouboulis CC, Saborowski A, Boschnakow A. Zileuton, an oral 5-lipooxygenase inhibitor, directly reduces sebum. 2005;210(1):36-8.

35. Surette ME, Koumenis IL, Edens MB, Tramposch KM, Chilton FH. Inhibition of leukotriens synthesis, pharmacokinetics and tolerability of a novel dietary fatty caid forumlatio in healthy adult subjects. Clin Ther. 2003;25(3):948-71.

36. Mak TN, Fischer N, Laube B, Brinkmann V, Sfanos KS, Mollenkopf HJ, Meyer TF, Bruggemann H. Poropionebacterium acnes host cell tropism contributes to vimentin-mediated invasion and induction of inflammation. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14(11):1720-33.

37. Vowels BR, Yang S, Leyden JJ. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines bya soluble factor of Propionibacterium acnes: implications for chronic inflammatory acne. Infect Immmun. 1995;63:3158.

38. Kim J. Review of the innate immune response in acne vulgaris: activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. Dermatology. 2005;211(3):193-8.

39. Mourelatos K, Eady EA, Cunliffe WJ, Clark SM, Cove J H. Temporal changes in sebum excretion and propionibacterial colonization in preadolescent children with and without acne. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(1):22-31.

40. Modlin RL, Godowski PJ, Sieling Pa, Cunliffe WJ, Holland D, et al. Activation of toll-like receptor-2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. J Immun. 2002;269(3):1535-41.